I. Overview

Ms. Carole Rosenlund (Regional Director & Head of Africa Section, International Center of Hydropower) opened the conference with an overview of the key trends in the hydropower segment in Africa, major issues and challenges faced by hydro projects, and the region’s hydropower outlook.

This set the ball rolling for the two-day summit.

The conference saw a series of presentations on the plans and perspectives of specific countries in Africa. Mr. William Willoughby Liabunya, (CEO, Electricity Generation Company, Malawi) gave an overview of the energy sector in Malawi, explaining how Malawi is uniquely well-suited for hydro energy production. While 90% of Malawi’s existing energy needs are met by hydropower, and in light of increasing energy demand, numerous further sites are being identified for new hydropower development.

Mr. Edward Iruura (Director-Financial Services, Electricity Regulatory Authority of Uganda) similarly explained how Uganda satisfies 79.8% of its energy needs by large hydropower plants, and another 12.2% by small hydropower projects. Uganda is pushing hydro development further with feasibility studies being conducted for 27 new projects, and 26 projects under development. Uganda is also taking initiatives to address major concerns of hydro developers, such as providing sovereign guarantees, standardizing PPAs, guaranteeing uptake, etc.

Mr. Taurayi Maurikira (CEO, Zimbabwe National Water Authority) spoke on the country perspective of Zimbabwe. He pointed out that Zimbabwe has some small hydro projects and a number of relatively small dams that the government was looking to convert into hydro energy projects.

A number of the presentations were also dedicated to discussing key hydropower technologies. Mr. Paul Hinks (CEO, MyHydro) gave a presentation on the company’s innovative Restoration Hydro Turbine, that allowed electricity generation with a water drop height of as low as 2 metres, compared to 40 metres for conventional mini-hydro projects. Mr. Aurelien Maurice (Leader, GE Hydro Solutions Digital) spoke about their flexible operation and management (O&M) solutions, that incorporated digital monitoring and information technology to lower maintenance costs and maximize production. Mr. Taurayi Maurikira (CEO, Zimbabwe National Water Authority) spoke on the potential of pumped hydro storage technology, which allows hydro energy to be used as a repository for energy generated by other sources. Mr. Paul Rollins (Director-International Business Development, Worthington Products Inc.) spoke about solving floating debris problems in hydropower with innovative technology such as weed booms.

On the second day, a number of presentations were focused on best practices and case studies. Mr. Stephen Dihwa (Executive Director, South African Power Pool Coordination Centre) spoke about hydro energy in the context of regional power trading. He explained that hydro energy had played a key role in driving power trading in southern Africa since hydro energy projects were naturally connected across borders. In fact, the bulk of the traded power in the South African Power Pool is from hydro plants. A number of large hydropower projects are expected to be developed in the region in the future as well.

Ms. Kellie Murungi (Chief Investment Officer, East African Power Corporation) spoke about the opportunity presented by small hydro. Small hydro has several advantages over large hydro, such as low environmental and social impact, ability to service remote areas, increased water efficiency, and scalability. At the same time, there are policy, development, and financial risks that hamper small hydro development. Better sovereign support for small hydro developers and aggressive early-stage financing were some solutions to mitigate these risks.

Ms. Eva Kremere (International Consultant, UNIDO) also spoke about UNIDO’s role in small hydro. She explained how Africa is uniquely suited for small hydro, as 70% of the new rural electricity supply was expected to be from off-grid or mini-grids. She explained through case studies how small hydro can fulfill this energy need, especially given its ability to stabilize the grid over other renewables.

Mr. Kassim Abubakar (Senior Electrical Engineer, Ghana Grid Company) & Ms. Afua Adwubi Thompson (Civil Engineer, Volta River Authority) spoke about transmission infrastructure requirements for upcoming projects in Ghana, while also giving an overview of the energy ecosystem and production capabilities of Ghana. Similarly, Ms. Ghada Osama (Head of Network Studies, Egyptian Electricity Transmission Company) spoke about the development and challenges to transmission in Egypt.

Mr. Moises Machava (Executive Director, Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa) presented a showcase on the International Hydropower Association, Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa, and the Mphanda Nkwua power project along with an overview of the Costa Rican energy ecosystem.

III. Presentation on Claims Management

The first day of the conference noted the opportunities and perspectives for hydropower across Africa. As claims are an inherent part of hydropower construction projects, Mr. Bagaria opened the second day with a session on claims management.

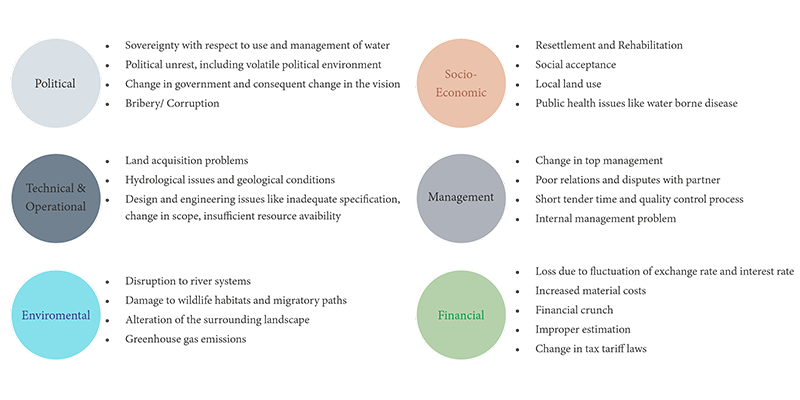

Mr. Bagaria began the session by noting the peculiarities involved in the hydropower sector. Hydroelectric power plants have complex structures and involve large amounts of capital with a long-running construction period. Unlike many other projects, hydropower requires more parts to be built simultaneously including the dam, power station, supply lines, etc. This situation imposes uncertainty factors with considerably high risks. Mr. Bagaria walked the viewers through the six categories of risks faced by hydropower projects.